Western Canada Geese

(Branta canadensis moffitti)

In the late 1980's the translocation of western Canada geese from Reno, Nevada to Humboldt Bay, California was initiated. The idea behind this translocation was to provide new hunting opportunities as well as minimize damage the geese were causing in Nevada. between 1987 and 1992, 645 geese were trapped near Reno and released on state wildlife areas around Humboldt Bay. By 1997 the translocated population had increased to 3,200 individuals and an annual hunt was initiated in September 1998.

During the semester, we encountered western Canada geese many times on field trips. We observed interesting behaviors such as triumph ceremonies and pre-flight signals. We were also fortunate enough to get up close and personal with an active nest and even float the eggs. Finally, we learned how to identify and read the collars on marked geese.

Triumph Ceremony:

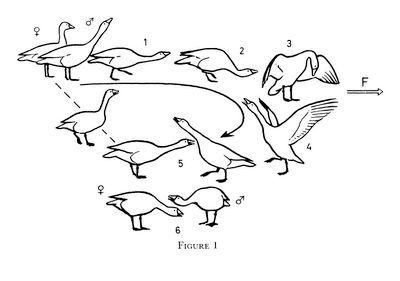

A triumph ceremony is a display put on by a pair of geese, usually after a female accepts a male's courtship displays or after a pair successfully defends or wins a fight over territory with another pair.

Pre-Flight Signals:

Geese communicate with their partners through a myriad of both vocal and non-vocal signals. When one member of a pair wants to communicate that they want to leave an area, it will signal to its partner with a series of head shakes, wing flaps, and vocalizations.

Collars:

Many western Canada geese in Humboldt county are equipped with plastic bands around their necks. These bands each have a unique combination of letters and numbers that identify the individual. With the use of these collars, the life history of each bird is tracked through its lifetime.

Griggs, K.M., J.M., Black. 2004. Assessment of a western Canada goose translocation: landscape use, movement patterns, and population viability. International Canada Goose Symposium.

Aleutian Cackling Goose

(Branta hutchinsii leucopareia)

History:

Aleutian Cackling geese were once thought to be extinct until Robert Jone discovered a population on Buldir Island in 1962. The original cause for decline was the introduction of foxes to the Aleutian Islands by the Russians to supplement the fur trade industry. The geese were not adapted to terrestrial predators and were, essentially, sitting ducks and easy prey for the foxes. The foxes decimated the goose population to the brink of extinction.

Aleutian Cackling geese were once thought to be extinct until Robert Jone discovered a population on Buldir Island in 1962. The original cause for decline was the introduction of foxes to the Aleutian Islands by the Russians to supplement the fur trade industry. The geese were not adapted to terrestrial predators and were, essentially, sitting ducks and easy prey for the foxes. The foxes decimated the goose population to the brink of extinction.Recovery:

Once this remnant population was found, there was an immediate move towards recovery of the species. The recovery strategy took a two-pronged approach. Beginning in 1963, a captive breeding program was established and Fish and Wildlife began removing foxes from the islands. Aleutian Cackling geese were listed as an endangered species in 1967 and, in 1973, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act which helped garner more protection for the species. One year later, in 1974, recovery efforts were ramped up and captive breeding efforts, pair relocations, banding, and research intensify. In 1975, the hunting season on all Canada-like geese was closed in the Sacramento Valley in an attempt to avoid any incidental loss of Aleutians.

Once this remnant population was found, there was an immediate move towards recovery of the species. The recovery strategy took a two-pronged approach. Beginning in 1963, a captive breeding program was established and Fish and Wildlife began removing foxes from the islands. Aleutian Cackling geese were listed as an endangered species in 1967 and, in 1973, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act which helped garner more protection for the species. One year later, in 1974, recovery efforts were ramped up and captive breeding efforts, pair relocations, banding, and research intensify. In 1975, the hunting season on all Canada-like geese was closed in the Sacramento Valley in an attempt to avoid any incidental loss of Aleutians. Success!

Thanks to the intense recovery efforts that took place over nearly 40 years, the Aleutian Cackling goose population had a successful recovery. In 2001 the species was removed from the ESA. Unfortunately, the recovery efforts were so successful that the species went from being and endangered species on the brink of extinction, to a pest.

From Success to Pest:

The Aleutian Cackling goose population has exploded to more than double the target population size of 60,000. Their spring staging grounds have also shifted with the growth of their populations. Instead of staging strictly in the San Joaquin Valley of California, they have worked their way up the state to Humboldt and Del Norte counties in addition to 3 sourthern Oregon counties. The geese are drawn to the high quality cattle grazing land available in this part of the state, much to the ranchers' dismay. With the huge numbers of geese grazing the pasture land, the traditional rotation employed by the ranchers is thrown off and less grass is available to the cattle.

The Aleutian Cackling goose population has exploded to more than double the target population size of 60,000. Their spring staging grounds have also shifted with the growth of their populations. Instead of staging strictly in the San Joaquin Valley of California, they have worked their way up the state to Humboldt and Del Norte counties in addition to 3 sourthern Oregon counties. The geese are drawn to the high quality cattle grazing land available in this part of the state, much to the ranchers' dismay. With the huge numbers of geese grazing the pasture land, the traditional rotation employed by the ranchers is thrown off and less grass is available to the cattle.

During our field trip to Pete Busman's ranch, we were able to get a real rancher's perspective. He talked to us about how he feels about the geese, what he thinks should be done to

manage their populations on private lands, and gave us examples of some of the hazing techniques he has used.

Hazing Techniques:

Mini, A. E., and J.M. Black. Expensive traditions: energy expenditure of Aleutian geese in traditional and recently colonized habitats.

Mini, A.E., K.M. Griggs, and J.M. Black. 2011. Recovery of the Aleutian cackling goose Branta hutchinsii leuccopareia: 10-year review and future prospects. Wildfowl 61:3-29.

American Wigeon

(Anas americana)

American Wigeons weren't really a huge topic of discussion during this semester. We were able to see them on a couple of field trips to the marsh and to the Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge. The supplemental paper posted to Moodle by Berl and Black (2011) pertained to vigilance behavior of American wigeons foraging in pastures.

This paper assessed Wigeons' vigilance behavior relative to where they were foraging. Vigilance of birds foraging on or near water was compared to those foraging on pasture land. It was found that vigilance behavior of American Wigeons increased significantly the farther away the birds are from water. Additionally, the birds were more vigilant after being away from the water for an extended period of time to the point of ceasing foraging all together for a period of time upon return to the water. Finally, male American Wigeon were more vigilant than females while foraging away from water.

Berl, J.L., and J.M. Black. 2011. Vigilance behavior of American Wigeon Anas americana foraging in pastures. Wildfowl 61:142-151.

Tundra Swan

(Cygnus columbianus)

The tundra swan was another species that was only briefly touched on in class this semester. We briefly discussed the tracking of migrating tundra swans via the use of coded neck bands like those used on the western Canada geese. Unfortunately, we were never able to see any of these birds while out on any of our field trips.

In the supplemental paper posted on Moodle by Black et al. (2010), the behavior of wintering tundra swans in the Eel River delta and Humboldt Bay is described. UsingChristmas Bird Counts, Black et al (2010) tracked the population size of tundra swans wintering in the Eel River-Humboldt Bay area from 1963 - 2009. They found that the highest number of swans, on record, was 1,500 occurring in 1988. Black et al. (2010) estimated the current population to be 96,200 birds. They also concluded that 1.1% of the population utilizes the Eel River-Humboldt Bay area to winter. Because this percentage is greater than or equal to 1%, this site is considered important.

In the supplemental paper posted on Moodle by Black et al. (2010), the behavior of wintering tundra swans in the Eel River delta and Humboldt Bay is described. UsingChristmas Bird Counts, Black et al (2010) tracked the population size of tundra swans wintering in the Eel River-Humboldt Bay area from 1963 - 2009. They found that the highest number of swans, on record, was 1,500 occurring in 1988. Black et al. (2010) estimated the current population to be 96,200 birds. They also concluded that 1.1% of the population utilizes the Eel River-Humboldt Bay area to winter. Because this percentage is greater than or equal to 1%, this site is considered important. Additionally, Black et al. (2010) calculated a time budget for the wintering swans. It was determined that the swans spent 44.9% of their time foraging, 22.1% consisted of comfort behavior, 16.2% spent on locomotion, and 15.5% on vigilance.

Black, J.M., C. Gress, J.W. Byers, E. Jennngs, and C. Ely. 2010. Behavior of wintering Tundra Swans Cygnus columbianus columbianus at the Eel River delta and Humboldt Bay, California, USA. Wildfowl 60:38-51.

No comments:

Post a Comment